The Deal That Never Closed Because Of My Blindspot

Three years ago, I lost a deal that could have changed everything. Not because of money. Not because of timing. Because I didn't know who had the right to say no.

We were three months into negotiations on what I thought was a game-changing partnership.

The kind of deal that would take our family business to new heights. Contracts were ready to sign.

Then came the voicemail. Thirty seconds that killed three months of work.

Before I could even call back, I found emails in my inbox shutting down the deal. Unfounded fears from people I did not know at the time were permitted to be decision makers about a deal they knew nothing about.

That's when I realized I'd made a massive assumption about something fundamental:

Who actually had the right to say no?

I thought I knew how decisions worked in our family business. Turns out, I didn't have a clue.

I'd communicated only with the chairman. I assumed that was enough. I expected the process to be straightforward.

(There's a lesson there about assumptions in family businesses.)

That failure taught me something I now apply to every team I'm part of. It's called a Decision Tree, and it's become one of my favorite tools for bringing clarity to chaos.

Here's how it works:

Before any major decision, we map out four simple questions:

Who has the right to say "no"?

Who gives input before the decision is made?

Who gets notified after?

Who doesn't need to know at all?

We put this in a simple spreadsheet. We discuss it with relevant stakeholders. And it's transformed how we operate.

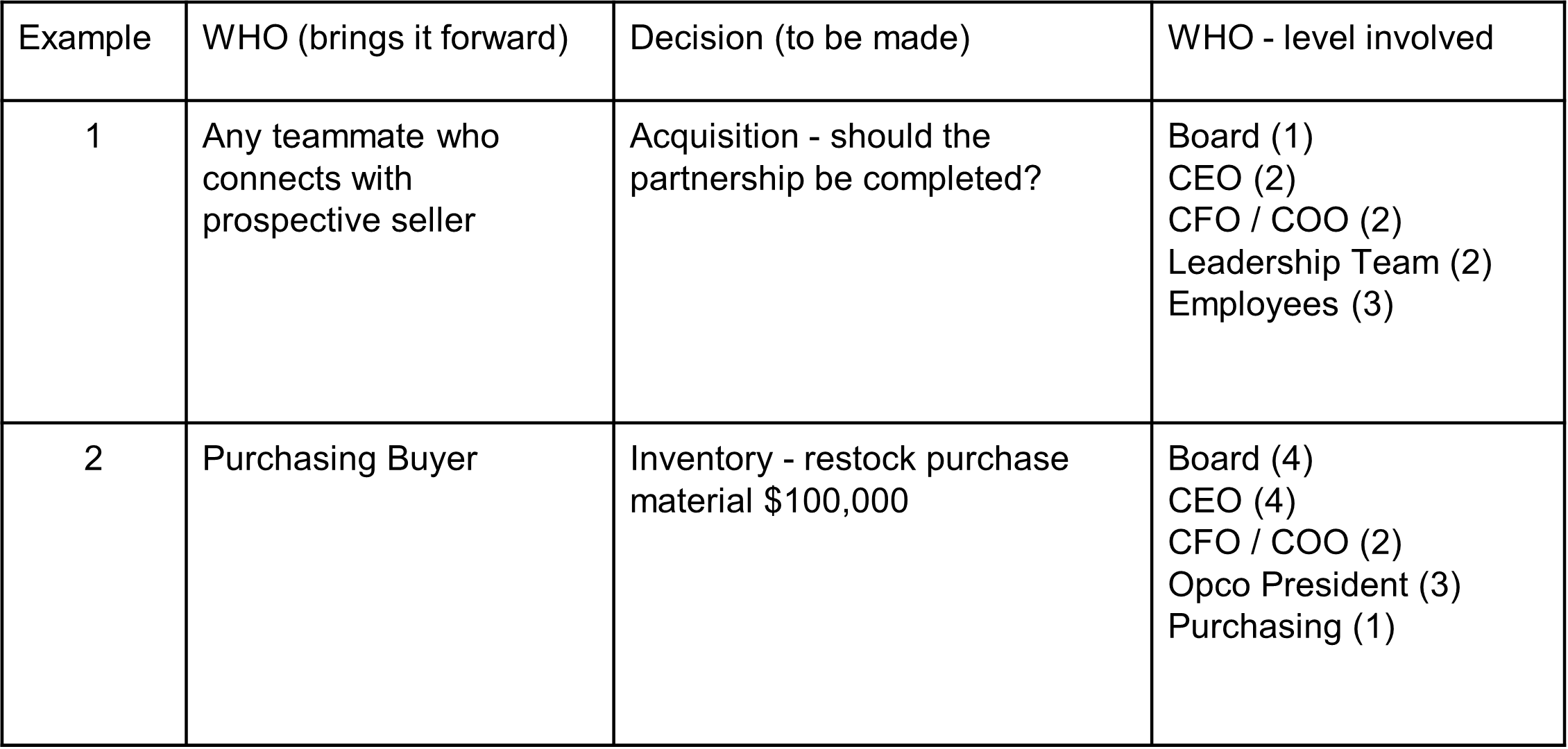

Here's what it looks like in practice: (each company/ culture is different)

Key:

1 = Right to say "no"

2 = Give input before decision

3 = Notified after decision

4 = Don't need to know

How the numbers work:

1 = right to say “no”

2 = give input before decision made

3 = make the decision and let me know after

4 = do not want to know about it

See the difference?

A major acquisition — strategic and irreversible — flows up to the board level. But a routine inventory purchase? That lands exactly where it should: with the person hired to make that decision.

The best leaders aren't the ones who make every decision. They're the ones who know which decisions to make — and which ones to give away.

Great companies don't necessarily make perfect decisions all the time. But they make lots of decisions quickly and iterate along the way. They differentiate between big, permanent choices and everyday operations.

(My five-year-old will remain a "3" for candy allocation, by the way.)

Building this kind of clarity compounds over time. Trust grows. Speed increases. People feel empowered rather than micromanaged.

And you never have to learn the way I did — with a voicemail that kills months of work in less than a minute.

Who can you empower this week to hold the "1" in a decision that matters?

Onward,

Matt